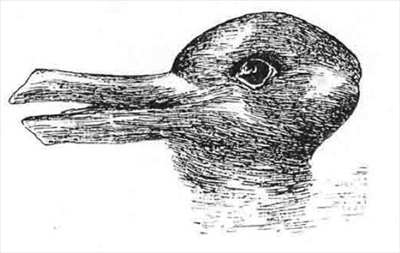

Martti Koskenniemi, admittedly, is not a household name. His work, however, touches upon our daily lived experiences. Koskenniemi is a giant among contemporary and historical legal scholars whose manuscripts, articles, and interventions draw upon history, international relations, and politics making them unique contributions to the field of international law and liberal intellectual thought. It is therefore a special treat not only to meet Koskenniemi but to watch him engage with legal scholars who are each engaging with his rich body of work. Last week, I enjoyed that unique privilege at Temple Law School, where Professor Jeff Dunoff, a stellar scholar and generous friend, organized a two-day Workshop entitled, Engaging the Writings of Martti Koskeniemmi. The program reflected the breadth of Koskenniemi's intellectual prowess and was divided into six panels: Using International Law in Times of Crisis; On Formalism in International Law: Reconsidering Fragmentation in International Law; Writing International Law: Questions of Cross- And Inter-Disciplnarity; Reflections on the Theory and Practice of International Law; and International Law, History, And Progress. Workshop participants drafted papers that challenged, built and reflected upon Koskenniemi's work. They delivered them in private to a company of their peers all the while striving to avoid speaking directly to Koskenniemmi who sat, without fanfare, on one of the edges of the square-shaped seating arrangement. Koskenniemi did participate in the discussions that followed the presentations and provided new insight into his ever-evolving thinking and approaches underpinning the dynamism of legal thought generally. The highlight for me, and perhaps for the rest of the participants, was his opening keynote address, wherein he discussed his ongoing seven-year book project on the history of legal thought. The lecture, Histories of International Law - Significance and Problems for a Critical View, lasted for what felt like only minutes and left me convinced that I should not write another word until I spent the next five years immersed in a disciplined reading practice. Below I include my notes from his momentous lecture. Koskenniemi began by explaining that each day he reads the newspaper, he thinks to himself that nothing interesting has happened since the French Revolution; at least nothing that has fundamentally changed the course of history and international law. There was a moment for such a shift in the nineties, when the atrocities in Rwanda and Yugoslavia prompted the creation of international criminal tribunals and hinted that international law would never be the same. However, since then, and especially since 2001, there has been a backlash that stunted that nascent development. Evaluating where we are today without the benefit of history would accept the "naturalness" of our present-day institutions, but they are not natural at all. To discuss that history, Koskenniemi divided his talk into three parts: the first part would look at the shoulders of giants in legal thought; the second would interrogate the Eurocentrism of legal thought; and the third would look beyond contextualism to ask then what? He begins by insisting that the history of legal thought reflects a teleological tradition. That teleology was first captured in religion and then by Hugo Grotius in international law, later by Immanual Kant as a set of principles and theories extrapolated from international law, and today in the form of the UN Security Council and other institutions that embody international law. In contrast, the Realist Tradition, using William Grave as a reference, contends that international law emanates from an imperial center to an imperial periphery. At the heart of that imperial activity is war and diplomacy. Legal history is therefore a history of empire. Taken simply, however, this would discount the fact that the center of empire is divided against itself as history demonstrates that the imperial periphery has used empire's law to challenge its core. To assume that international law's history is one of imperial domination and control is as reductionist as assuming that its history is an idealistic one about the pursuit of freedom, dignity, and justice. Koskenniemi then moves on to highlight the Eurocentrism of international law which complicates this sordid history. He explains that one cannot imagine international law without a European imaginary- this includes the Renaissance, Jus Gentium, the earliest concept of sovereignty, and the seeds of international law found in Roman courts and the works of Cicero. Lawyers on the imperial periphery, however, like T.O. Elias of Nigeria and R.P. Anand of India, are also part of international law's development and history. Koskenniemi explains, however, that insofar as they shaped the substance of international law, they did so within its confines thereby asserting that "we are also European." Another approach is to tell the stories of colonial barbarism that spurred an anti-colonial consciousness. Yet another approach is a hybrid one that includes both the imperial center and the periphery's pushback that created a dialectic of international law. As a historian of legal thought these approaches present problems because today we view international law as the body that exists in front of us. However, this approach or Presentism, risks skewing history. Koskenniemi continues that it projects our conceptions or present-day readings onto people who were free from those ideas and readings all together. Worse, it influences legal thinkers to willfully ignore what these historical figures were trying to say at the time they were saying it. Hugo Grotius is a great example in this regard- he served as a legal adviser to the Dutch East Indies Company and he considers his greatest contribution to be the unification of churches and yet, international lawyers, in particular, regard him as the forefather of international law. Despite the risks posed by such historical readings, we continue to place all sorts of diverse writers into a single tradition that we can then step into ourselves. So where does that leave historians who want to write about the history of international law? Koskenniemi suggests that writers should be concerned with scope and scale. This involves choosing where to begin and what scope of it to examine. In his own forthcoming book on the history of legal thought, Koskenniemi will begin with a discussion of St. Augustine and an examination of international trade. While sovereignty and trade are two aspects of the history of international law, there has been an undue attention given to soveriegnty. However, he explains, "I look at the Netherlands in the sixteenth century and I see a company," sovereignty is indeed relevant but only later in the game. Additionally, a constant challenge will be how to accurately describe historical figures of legal thought. Take Vittoria for example: was he a counter-reformationist or was he a teacher? Tony Anghie has been accused of presentism in his writings on Vittoria for imposing a particular context upon him. However, Koskenniemi counters that there is no absolutely right context- the content of our writings reflects what is most relevant to our own chosen scope and scale. It is similar to looking at this perennial image that challenges the objectivity of our perspective: Is it really a duck or a rabbit? Does it matter?

Koskenniemi continues that as legal historians, we are writing a history of the present; the writing practice itself reflects a desire to intervene in the present. Despite his desire to make such an intervention, Koskenniemi then ends on an anti-climactic note and explains, "The world is a disaster and I have nothing to offer to help you figure it out. My work is that of a detective...to say who dunnit?" Perhaps he is right, but it is doubtful that future generations of international lawyers, historians, and writers will look so plainly upon Koskenniemi's work. Surely, their own presentism will shape him into something more than a detective and, instead, as a culprit of spurring radical approaches to the study and practice of international law.

1 Comment

On April 6 and 7, 2013, activists, scholars, and community members will converge at Boston University to participate in the Right of Return Conference at Boston University. The last Right of Return Conference took place in Boston more than a decade ago and featured the late Edward Said as its keynote speaker. This Conference is especially critical at this juncture as the Oslo Peace Accords turns twenty and in the direct aftermath of President Barack Obama's first visit to Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory in his two-year term. The Oslo Accords sought to establish two ethno-nationally homogenous states as a remedy to Israel's settler-colonial regime. Not only did the Plan fail to deal with the root cause of conflict in the region but it also failed to thwart the ongoing forced displacement of Palestinians both within Israel Proper as well as the Occupied Palestinian Territory. In the shadow of the Peace Process, for example, Israel has accelerated its Judaization campaign of East Jerusalem, where it administratively revoked the residency rights of 4,800 Palestinian Jerusalemites in 2008 alone. Oslo excluded refugees from its consideration all together when it relegated the fate of 6.6 million Palestinian refugees to final status negotiations which remain elusive. Since then Israeli officials, like Avi Dichter have made clear that the return of refugees is a red line in any negotiated solution. In response to a PA officials mention of refugees in 2011, Dichter declared “The 'right of return' will not be included in the peace process... Talk about the 'right of return' is meaningless. Everyone understands that there will not be a solution that includes 'return,' no matter who says what.” The right to return, however, is not a political matter, it is a humanitarian one governed by international law and precedent. Those precedents include the return of, restitution to, and compensation of refugees to East Timor, Bosnia, and South Africa. Those laws include:

This speaks volumes to the vision of Conference's organizers who have remained on course despite significant political pressure. In an article published today on Mondoweiss, two of these organizers, Zena Ozeir and Jamil Sbitan explain: As aptly argued by Edward Said 13 years ago, this failure on the part of official channels precipitates the urgency that these matters be taken into the hands of non-governmental actors through independent planning and organizing. This is the framework from which the current upcoming Right of Return Conference at Boston University emerges; from an impetus to plan rather than debate the realization of the Palestinian Right of Return. Through examining the legal, cultural, discursive and spatial dynamics of a political order that facilitates this Right, this conference asserts the applicability of this goal, thus countering those who voice its supposed inapplicability. Check out the full conference schedule below. Better yet come through this weekend or join an effort to make real the return of Palestinian refugees. During my allotted time, I will be sharing some of the findings of Badil's comparative study tours that it has conducted in furtherance of that effort. Conference Schedule Saturday, April 6th 9:00 OPENING REMARKS 9:15 PANEL: “Discourses of Return and Resistance Among Palestinian Refugees” Moderator: Sa’ed Atshan Charlotte Kates & Khaled Barakat: Return and Liberation, Liberation and Return: The Palestinian National Movement and the Implementation of Return Ziad Abbas: Palestinian Refugee Youth and the Legacy of Right of Return Sarah Marusek: Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon: Somewhere in between Rights and Resistance 11:00 PANEL: “Identities on Display: Collective Identity and Daily Practice” Moderator: Amahl Bishara Joseph Greene: The Palestine Archaeological Museum: Disentangling Cultural Heritage “After the Return” Riccardo Bocco: Collective Memory and Dreams of Return: A Journey through Documentary Films Portraying Palestinian Refugees 12:30 LUNCH BREAK 1:30 Keynote Speech: Dr. Salman Abu-Sitta 2:30 PANEL: “Paradigmatic Shifts: Jewish Identity, Theology, and Liberation Post-Return” Moderator: Eve Spangler Bekah Wolf: Re-Visiting Self-Determination Cory Faragon: Meusharot, Knafonomics and the Right of Return Yakir Englander: “Choose Life”: The Imperative of a New Jewish Theology of Return 4:30 PANEL: “Deconstructing Colonial Narratives: Navigating Space, Peoplehood, and Origins” Moderator: Heike Schotten Alborz Koosha & Lila Sharif: Land and Peoplehood(s): Countering Zionist Settler Origin Stories for a Post-Return Palestine Linda Khalil & Sarona Bedwan: Negotiating Space: Deconstructing Palestinian Identities & Illuminating Ways of Being 6:00 CLOSING REMARKS Sunday, April 7th 9:00 OPENING REMARKS 9:15 PANEL: “Disappearing and Reappearing: Refugees Between NGOS, Legal Status, and Return” Moderator: Susan Akram Anne Irfan: Handing Back the Keys: UNRWA and the Right of Return Jinan Bastaki: Disappearing Refugees and the Legal Gaps: The Implications of Third Country Citizenship for Palestinian Refugees and the Right of Return 10:45 PANEL: “Imagining Spaces of Return & Mapping Palestinian Liberation” Moderator: Salim Tamari Linda Quiquivix: Liberation or Independence: Palestine as Land or Palestine as Territory? Einat Manoff: Counter-mapping and the Geographical Imagination: Mapping Spatial Scenarios of Return Thomas Abowd: The Return of Homes and the Restitution of History in Jerusalem 12:45 LUNCH BREAK 1:45 Keynote Speeches: Noura Erakat (Badil) & Liat Rosenberg (Zochrot) 3:30 PANEL: “Rehabilitating the Body Politic: Palestinian Politics and Models for Return” Moderator: Leila Farsakh Sadia Ahsanuddin: Restitution in the Land of Milk and Honey: Implementing the Palestinian Right of Return via Israeli-Palestinian Federalism Sarah I.: Who Is A Palestinian? Political Representation of the Shatat in the Homeland 5:00 Keynote Speech: Dr. Joseph Massad 6:00 CLOSING REMARKS  Maysara Abu Hamdieh died yesterday in the intensive care unit of the Israeli Soroka Hospital due to medical neglect in Israeli custody. Maysara, who had been held in administrative detention several times before his deportation to Jordan, was serving a life sentence at the time of his death. His health seriously deteriorated only two years into his sentence in 2007. The Israeli Prison Service (IPS) failed to provide him adequate medical attention and care, including access to regular medical examinations. Maysara's death is not an exception but part of Israel's systemic ill-treatment of its Palestinian detainees. He is the 5th prisoner to die in Israeli custody due to medical neglect in the past 2 years bringing the total number of Palestinian prisoner deaths to 207, including 52 who have died as a result of medical neglect. At present, approximately, 1,000 of the approximate 4,600 Palestinian prisoners suffer from illness, including 25 who suffer from cancer. The Fourth Geneva Convention obligates an Occupying Power to provide adequate food and medical care to detainees in its custody, (Art. 91 and 92). Failure to do so in ways that evidence willful killing, torture, or inhuman treatment constitute grave breaches of the Convention and are tantamount to a war crimes. The Palestinian Human Rights Organization Council (PHROC) calls upon the international community to respond accordingly to the death of Maysara and the ill treatment of all Palestinian political prisoners. In its statement issued today, it explains: The PHROC therefore demands that the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon immediately intervene and form an international committee charged with investigating the circumstances surrounding the health of and medical care provided to Palestinian prisoners and detainees in Israeli custody, as well as the circumstances of the Maysra Abu Hamdiya’s death, and intervene to secure the release of all sick prisoners. |

CurrentsThis is my semi-personal journal of travel, observations, & encounters! Archives

January 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed