|

Can the International Criminal Court (ICC) deliver the justice Palestinians have struggled to realize for well over a century? The pursuit of accountability at the ICC is one venue of this struggle. But any sustainable vision of Palestinian liberation must account for the confines of the courtroom in particular international law more broadly. As should be clear to all observers of international law, the odds are stacked against Palestinians in that courtroom. The challenge ahead is to innovate not simply litigation strategies but to put them in conversation with radical popular mobilization.

The move to the ICC does offer Palestinians two significant opportunities. One, it allows the Palestinian Authority (PA) to once and for all abandon US tutelage once. Since the Oslo Accords and its attendant processes created the PA in the 1990s, the nominal Palestinian leadership has relied exclusively on the United States as its patron saint. This reliance, and indeed the PA’s very existence as a product of Oslo have foreclosed the pursuit of self-determination. Instead the PA and the Oslo process nourished Israeli settler-colonialism, apartheid, and military occupation. Two decades of escalating Israeli political and economic dominance has left the PA with ever-shrinking space to maneuver. The turn to the ICC comes in many ways as a response to this externally—and to some extent self-imposed—straitjacket. The turn to the ICC will expose Palestinians to several vulnerabilities. Yet it also offers the PA another golden opportunity: to once and for all turn away from its investment in an ostensible peace process that has served to buttress a small circle of elite interests and return once again to the pursuit of self-determination. Such a pursuit would not preclude the possibility of a political solution. It would enhance the Palestinians’ negotiation leverage. Despite rumblings for several years, PA President Mahmoud Abbas’s signing of the Rome Statute on the last day of 2014 came as a surprise to most observers. Until late 2014, the PA dangled criminal accountability as little more than a loaded threat in the vacuous remnants of a liberation strategy that the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) has abandoned since signing the Oslo Accords. Legal, grassroots, media, and popular mobilization fell to the wayside. On the legal front, such a strategy would include advocacy within the United Nations General Assembly, the advancement of human rights norms, the insistence upon adherence to international law, and cooperation with multilateral human rights organizations. It would also include supporting civil society representatives among human rights treaty bodies, and innovative claims within the International Court of Justice (ICJ) as well as in foreign national courts. The grassroots component includes support for local efforts aimed at building solidarity, including but not limited to Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) efforts. A media strategy involves globally taking on Israeli hasbara efforts through print, audio, television, and social media. The PA turned its back on these strategies and adopted a narrow political emphasis rooted in an unequivocal faith in realpolitik. This faith effectively positioned the United States, in its capacity as world superpower and Israel’s primary patron, as the only party capable of delivering a Palestinian state. In practice, this strategy is the strict adherence to the US-brokered bilateral process, which lacks any reference to international law, external review mechanisms, and is dictated by expedience and pressure. In this iteration, the political is a narrow realm that dismisses the law and its attendant normative values as impediments to the possibilities of a political solution. Since 1993, at least, the Palestinian leadership has bought into this understanding of the political and left itself with no negotiating leverage. Indeed, the PA has chosen time and again to prioritize realpolitik over any pursuit of legal accountability. There are many examples of these choices. In 2009, the PA rescinded the Goldstone Report from the United Nations Human Rights Council and turned its back on popular calls for criminal accountability as well as a review of Israel’s use of conventional weapons, and its non-adherence to the Fourth Geneva Convention. The PA also failed to leverage one of its most significant legal achievements, the 2004 ICJ Advisory Opinion on the route of the Separation Barrier and the situation in the Occupied Territories more generally. The PA showed no interest in using the ICJ’s recommendations to encourage states to cease all trade with Israeli corporations that facilitate the expansion of the wall or the entrenchment of its settlement infrastructure in the West Bank. The Palestinian leadership looked the other way when 170 civil society organizations assumed the mandate issued by the ICJ to states and launched the boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) movement. The PA’s legacy of legal advocacy is one of missed opportunities and opportunistic failures. Since Israel’s twenty-two day aerial and ground onslaught on the Gaza Strip in 2009, the Palestinian leadership has invoked ICC prosecution as a threat of last resort should the United States (continue to) fail to deliver its political guarantees. The concern in this last ditch turn is that the two decades of abandoning legal strategy means that the PA has not invested in its study, development, or preparation. It is likely ill prepared to tread the many pitfalls of an ICC investigation. The multilateral body, which is highly vulnerable to state interests and interventions, is replete with the trappings of legal technicalities. It cannot be a panacea to Palestinian claims for accountability. To successfully pursue ICC prosecution of individual Israelis on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity, the PA must launch a multifaceted campaign that positions the courtroom in a broader vision of political mobilization. These efforts should support the ICC process, while looking far beyond it. ICC jurisdiction itself is not a silver bullet and may even prove more detrimental than beneficial. If the PA is to pursue claims within the ICC, it must do it within a broader commitment to resisting Israel’s apartheid regime and military occupation. The law is a realm of both possibilities and obstacles, in particular in its inability to proximate non-legal justice. As David Luban, Michael Kearney, and others have shown, this is just as true for the ICC as any other venue. Here, I highlight these stumbling blocks and conclude with recommendations for viable legal strategies. Stumbling Blocks on the Road to ICC Investigation and Prosecution Scope In 2009, the Fatah-dominated PA attempted to give the ICC ad hoc jurisdiction over Israeli crimes in the Gaza Strip during Operation Cast Lead. The ICC declined, stating that “only states can join the ICC or give ad hoc jurisdiction, and we cannot yet decide that Palestine is a state.” Since then, Fatou Bensouda was appointed ICC prosecutor. In August 2014, she signaled her willingness to consider a new application by Palestine. The November 2012 UN General Assembly vote, when 139 member states recognized Palestine as a state, may settle the question of statehood. The recognition of the state of Palestine renders an occupied territory as a viable entity. The evocation here of Palestine is one tinged with irony. The law has made its evocation before international legal institutions and multilateral bodies possible, while Israel both continues to deny and diminish its sovereignty. On 31 December 2014, Palestine deposited a 12(3) application accepting the ICC’s jurisdiction since 13 June 2014 and acceded to the Rome Statute. Unlike in 2009, in late 2014, Palestine committed itself to the Statute’s provisions and potentially made the entirety of the situation in Palestine, the West Bank including East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip, subject to review. As such, the ICC can investigate both Israel as well as Palestinian armed groups. Here, the law reifies the power imbalance between the occupying power and the occupied. However, some legal analysts have argued that only prosecuting Israel would be counterproductive for Palestinians. In this rationale, such a strategy would undermine the court’s legitimacy in the eyes of the world’s most powerful, and skeptical states, not least of which is the United States. Significant here of course is that of its (now) 123 parties, “Brazil is really the only large state in the world that is a member of the ICC.” Moreover, “more than half the world’s population lives in countries that do not belong to the ICC.” Here then, we see the vulnerability of the ICC. It has the potential to become a strong body but is reliant on the world’s strongest non-member states to determine the scope of its legitimacy. Investigating War Crimes The fact that the ICC can examine the entirety of the Palestinian territories is actually a positive development. Israel’s structural violations in law and policy and not simply its engagement in armed conflict become subject to scrutiny. Crimes that belligerents commit during wartime are the most difficult crimes to investigate. Their legal character is not self-evident. For example, the ICC would have to examine each of Israel’s military attacks on a case-by-case basis. This examination would entail a consideration of whether military harm outweighed the pursued military advantage. Thus the court must have access to military intelligence that both Israel and Palestinian resistance armed groups would not provide. More crucially the emphasis on the idea of “military advantage,” without examining the context in which that force is being used, itself legitimizes the use of armed violence and once again reifies the power imbalance between the colonizer and the colonized. Legally, the conduct of Palestinian groups is easier to decipher. Palestinian rockets lacked the capacity to distinguish between military and civilian objects. Their use is thus ipso facto illegal. In contrast, Israel insists that it sought to avoid civilian casualties. This claim, while unevidenced, would necessarily complicate the legal readings of Israeli military action. Should Israel choose to participate in these proceedings, it will be eligible for making a case in contrast to Palestinian armed contingents. This has significant implications for Hamas, which governs the Gaza Strip and is one half of the desired, and necessary, Palestinian unity government. Its leadership will be the primary target of an ICC investigation and should the investigation lead to their prosecution, it will delegitimize their participation in government. Depending on who is prosecuted, it may have the effect of delegitimizing Hamas all together. Hamas recognizes this risk and has endorsed the ICC bid. Still, the Palestinian leadership should be prepared for this outcome and its impact on a unity government. Palestine, as the ICC recognized it, is also at a disadvantage because of its inability to demonstrate that it can adequately investigate and prosecute its own alleged crimes. For this reason, the provision of complementarity, which affords the ICC jurisdiction only over cases where the state “is unwilling or unable to genuinely carry out the investigation or prosecution,” is—for all intents and purposes—moot. In contrast, Israel can make a case for complementarity. Specifically, it can argue that it is willing and able to investigate itself, as evidenced by its five ongoing criminal investigation into Operation Protective Edge. Together with its inclusion of non-military personnel in its military commissions, as established during the Turkel Commission, Israel could argue that these are genuine investigations. While Israel’s dismal record of investigating its own war crimes during Operation Cast Lead puts the adequacy of complementarity into question, to demonstrate that inadequacy would involve a separate and lengthy legal process. The principle of complementarity would at best shield Israel from ICC investigation and at worst, delay the process so severely as to thwart justice. ICC Prerogatives Even if the ICC could adequately investigate Israel’s alleged war crimes in during the summer of 2014, and assuming that it could demonstrate that Israel’s own investigations were not genuine, that does not guarantee an ICC investigation into the matter. The court may still choose to avoid the political landmines of walking into the Palestinian-Israel conflict, and, as put by Kevin Jon Heller, “slow-walk the preliminary investigation intooblivion.” The Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) exercises significant discretion in deciding which cases and situations to investigate. Should the prosecutor find that a criminal investigation would not serve “the interests of justice” because it would hamper an ongoing political process or fail to adequately satisfy any party thus exacerbating the situation, she could simply delay the preliminary review process so severely as to make it irrelevant. Heller points out that this was the case in Afghanistan and Colombia: Afghanistan was moved from phase two to phase three after seven years. In other words, it supposedly took seven years for the OTP to conclude that at least one international crime was committed in Afghanistan. You and I could have completed phase two in a lazy afternoon with tea. Photos of torture at Bagram Air Force Base would have been enough. Even one Taliban killing would have been enough for phase two to move to phase three, and yet it took the OTP seven years. Even worse, Colombia is still in phase three of the preliminary investigation after ten years, even though every human rights group inside and outside of Colombia agrees that the Colombian government is doing nothing to investigate and prosecute high-level perpetrators of violence in the country, particularly those that are linked to the government itself. There is nothing to shield Palestine from this outcome. This possibility should temper faith in the ICC’s ability to deliver justice. Investigating Settlements The Palestinian leadership can refer a specific situation to the ICC for investigation. Rather than refer the situation of the Gaza Strip or of Palestine, the Palestinian leadership could refer the situation in the West Bank only in order to limit the ICC’s investigation to the question of settlements. This may be preferable to prosecuting Israel for alleged crimes committed during Operation Protective Edge because it circumvents the difficulties of investigating military operations during hostilities. More importantly, a limited referral would bypass the hurdle of complementarity because Israel will investigate neither settlements nor prolonged military occupation since both are explicit Israeli state policies. That said, a limited referral will still open Palestine to prosecution for suicide bombings launched from the West Bank and other alleged crimes under the Rome Statute. Moreover, even this option is not a silver bullet since the Prosecutor can exercise her discretion to reject this referral for limited review. She can choose to investigate the Gaza Strip only or both the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, putting us back at square one. While less complicated than the investigation of military operations, investigation of the transfer of civilian populations into occupied territories and the confiscation of land for that purpose will still raise considerable difficulties. These challenges include the impediments of bilateral treaties that the PLO and Israel have signed onto—namely Oslo II. Oslo II gave Israel military and civilian jurisdiction over Area C (of the West Bank), where Israel has aggressively entrenched its settler-colonial enterprise. The court is not likely to conclude that Oslo II overrides Palestine’s jurisdiction over the West Bank. As articulated by Darryl Li, Palestine did not delegate authority it had to Israel, but rather that the Occupying Power delegated its nominal authority to a temporary and local administrator, the PA. This is a lucid example of the irony of evoking Palestine as a state actor under the law. It exists as a forward-looking shadow without the ability to fully step into its own body. That still leaves (at least) two issues. First, what is the value of the land swaps, which the PA has indicated a willingness to accept, on the territorial scope of the Palestinian state? And do those potential land swaps matter in light of the UN General Assembly November 2012 recognition and subsequent diplomatic efforts across Europe recognizing Palestine? I imagine that if the ICC prosecutor chooses to investigate this case or situation that she will defer to the majority will of member states and recognize Palestine as existing within the 1949 Armistice Lines. Secondly, what does ICC prosecution mean for land confiscations? During an ongoing armed conflict and under Occupation Law, which govern the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, Israel can justify these confiscations. So Now What? Some Recommendations At present, Abbas has only signed onto the Rome Statute and deposited a 12(3) application that gives the ICC retroactive jurisdiction to 13 June 2014. He has not referred a situation or case to the Office of the Prosecutor. This may be the farthest that the Palestinian leadership actually goes and that would not be unwise. This holding position is forward-looking and serves as a deterrent to any future attack Israel may launch against the Gaza Strip. If, however, the PA chooses to refer a situation to the prosecutor, then it is best to refer one of structural substance. One possibility is referring the situation in the West Bank in order to focus on settlements. If the prosecutor accepts this limited review, it would avoid the possibility of complementarity as well as the many liabilities associated with the investigation of hostilities in the Gaza Strip. The ICC will not be the site of adequate redress for Palestinians. The likely scenarios include: the court slowly killing the referral in the inaccessible and lengthy intricacies of its proceedings; Israel evading prosecution through complementarity; the prosecution of alleged crimes committed by Palestinians only; and investigation of Israel’s settlement enterprise preceded or complimented by prosecution of Palestinians. These possibilities range from abhorrent to tolerable. The ICC cannot be a destination in and of itself. It is simply one venue, and a complicated one at that, of many. Any courtroom, including the ICC, can only be effective if it is one part of a broader commitment and struggle for self-determination and justice. This broader commitment and struggle is the only way to leverage any potential benefits ICC prosecution may offer. The isolation of Israel and the delegitimization of its apartheid regime and military occupation require a resistance platform. Such a platform would include the PA’s expansion of its legal strategy and its seeking of diplomatic partners to resist and withstand US sanctions. It would include the PA’s turning to civil society’s robust campaigns, such as but not only the global BDS campaign, for direction. It would include the PA’s dedication to a concerted media effort, as well as its investment in Palestine’s cultural workers, and in a agricultural resistance economy. Such an economy seeks to provide basic goods to Palestinians in the Occupied Territories and enables them to boycott Israeli goods and resist their formation as a captured market. It would include achieving an actually functioning realistic unity government with Hamas- one that envisions the possibility of ICC prosecution against its leadership and prepares for that attendant fall-out. Ultimately the best outcome of the turn to the ICC would be the PA’s extrication from the swamp that is Oslo and its reorientation toward Palestinian liberation. The worst-case scenarios are abundant. The PA could use ICC prosecution haphazardly and, more detrimental still, as weak leverage to continue the structural trap of bilateral negotiations. The best-case scenarios require diligence, resources, and a tremendous amount of good fortune. Most of all, they require the PA to turn away from its limited pursuit of self-interest. Such a dramatic shift among the Palestinian leadership offers much more promise for the pursuit of justice than any court could deliver. [An excerpt of this essay originally appeared in a MERIP roundtable on Palestine and the ICC.]

29 Comments

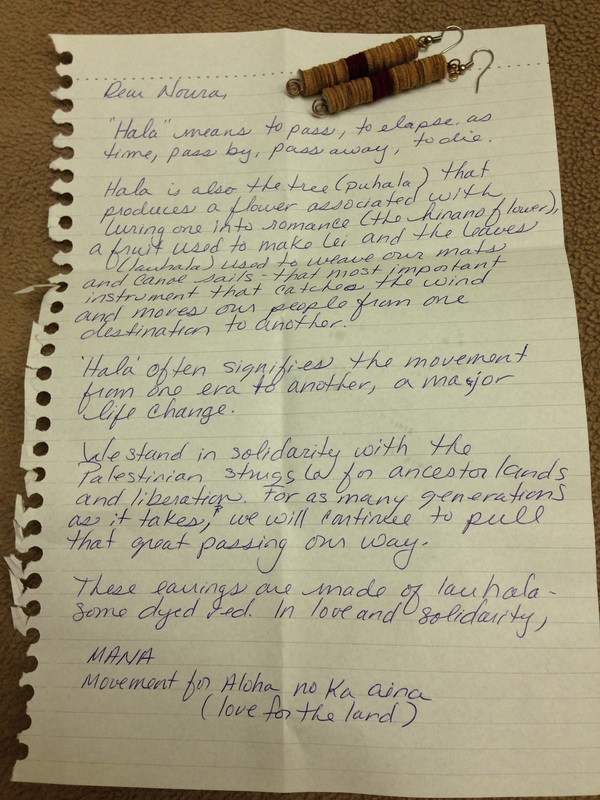

In late November 2014, I had the honor of visiting the occupied Kingdom of Hawai’i as aninvited guest. I prepared for the trip with ample readings J. Kehaulani Kaunaui both wrote and shared with me, along with book recommendations that my hostess, Cynthia Franklin, passed along. (It merits writing a separate article just about Cindy and her phenomenal skills as an organizer and her generosity as a friend. She is fire.) I thought my greatest challenge would be unraveling the competing independence paradigms, namely de-occupation and de-colonization, and understanding their relationship to indigenous nationhood. While we indeed delved into these issues, they were quickly eclipsed by something I could not prepare for: the island’s spirit. It must sound silly to reduce the violent, military takeover of a sovereign nation, the exploitation of its lands and waters, and the marginalization of its people to a metaphysical sensation. However, this is not to make light of the situation. To the contrary, by centering that spirit, I am emphasizing the gravity of these ongoing crimes and the righteousness of the resistance to them. The Kanaka Maoli, who today constitute twenty percent of Hawaii’s population, often express their relation to their lands with “aloha aina,” literally love for the land. Aloha, though neatly commodified to sell Hawai’i to tourists, represents a way of being deeply ingrained within native Hawaiian culture. It encompasses how you treat your neighbor, your family, how you maintain your relations with the elements that sustain life, and how you will to live. Aloha aina seems to translate neatly but is meant to capture a people’s sacred commitment to life, a way of life and a way of viewing life. In my five hurried days that included three lectures, several interviews, and generous dinners, I admittedly only caught a glimpse of that spirit. Yet, that glimpse gripped me almost instantly and I found myself beginning my lectures with confessions about the impact of this spiritual knowledge and how it scales hyper-intellectual conversations to their proper size. I began with a discussion about my family’s journey of displacement and exile, about how I came to be a settler in North America, and what it meant to visit the occupied kingdom in solidarity. No one flinched at my openness. It could not have been more proper, especially following the welcoming songs or the Oli–the Hawaiian ceremonial chants—that preceded my remarks. De-Tour: The People’s History of Hawai’i It was with this openness and spiritual awareness that I embarked on the De-Tour or Sovereignty Tour with local leaders and s/heroes, Kyle Kajihiro and Aunty Terri Lee Keeko’olani. The tour provides a critical history of the island and its most well-known landmarks. We happened to go on the tour on Hawaii’s Independence Day. On 28 November 1843, the United Kingdom and France recognized Hawai’i as a sovereign state by treaty. Hawaii’s formal sovereignty is precisely what makes it so unique. There is no contestation that it is occupied. Hawaii’s sugar oligarchy, represented by white American settlers, motivated the occupation. Seeking to remove the tariffs on their sugar exports to the United States, this oligarchy in collusion with the US Minister to Hawai’i, John L. Stevens, facilitated the landing of US Marines on Hawaiian shores to hold the Queen Lilioukalani hostage and take over the kingdom in 1893. US President Grover Cleveland refused to recognize the US military coup and takeover of Hawai’i and recommended restoration of the Queen. His efforts failed, and his successor, William McKinley, supported annexation despite fervent protest captured in petitions against annexation that were buried by colonial school curricula and only recently resurrected by Hawaiian scholar Noe Noe Silva. The United States formally annexed Hawai’i in 1898 although the annexation lacked legitimacy for being unilateral and not treaty based. It incorporated Hawai’i, and Alaska, into the United States in 1959. In 1993, one hundred years following the takeover, the United States issued a formal apology to native Hawaiians for the takeover of the Kingdom and the annexation of public and government lands without compensation. But the US government did nothing to remedy the situation. Hawai’i remains vital to the United States for military and strategic reasons. The United States has confiscated 1.8 million acres of the kingdom’s four million acres of land. It set aside a miniscule amount in trust for native Hawaiian benefit, measured by a distorting blood quantum, and uses the rest of that land for the expansion of bases or other military purposes. There are 118 military bases on Oahu alone. They take up twenty-six percent of the land or 230,000 acres. Beyond its territorial dominance, the United States uses Hawaii’s strategic position to maintain control over its Western border. It does so from its Pacific Command (PacCom), also known as the head of the octopus or he'efor being the largest unified US command. It extends from the US western coast to the Indian Ocean and from Alaska and includes all of Antarctica—it stretches over fifty percent of the earth's surface and includes forty-three countries. Pearl Harbor is part of this vast network and is the tip of the iceberg of the entrenchment of military-industrial complex in Hawai'i. It is so central to the economy that folks describe it as a necessary evil. The presence of military installations and retired personnel marks an elite demographic that shapes Hawai'i's politics. This includes subsidized housing for military personnel to the tune of three thousand US dollars per month and private malls, grocery stores, schools, and golf courses. Often times these luxurious benefits juxtapose dilapidated housing complexes for native Hawaiians who live communally. The Battle Over Water and Livelihoods US occupation of Hawai'i has had a tremendous impact on the flow and distribution of water. Taro—a wetland root—has been a staple among bad for native Hawaiians. The emergence of sugar plantations overseen by American oligarchs necessitated the diversion of water from those wetlands to more arid landscapes severely undermining indigenous agricultural practices and livelihoods. Elite interests unjustly also altered the flow of water throughout all of the islands thus impacting socio-political relations among Hawaiians as well. When sugar was no longer as profitable, ruling oligarchs shifted their businesses to tourism. The original waterways have never been restored though this battle continues. Brothers, Charles and Paul Reppun, have led several of these protracted battles. Together with their families, they oversee a sustainable farm on Oahu that we had the privilege and delight of visiting and tasting. Between 1913 and 1916, the Oahu Sugar Company built a ditch and diverted twenty-seven million gallons per day from the windward watersheds of the Koolau mountains to Oahu’s central plain to support sugar plantations. In 1995, the Oahu Sugar Company ceased its operations, thus sparking a legal battle to restore the streams and native stream life. The Reppuns, in coalition with other taro farmers and native Hawaiians led this battle. The Hawaiian Supreme Court twice vacated the Board of Water Supply’s (BWS) findings and recommendations citing their non-compliance with State Water Code and public trust principles. In 2006, the BWS issued a split decision that seems to reiterate its 1997 recommendations overturned by the Hawai’i Supreme Court in 2000. The BWS majority favors diverting the water for future yet-to-be-permitted uses like housing developments and tourist attractions. This is a battle between a way of life, livelihood, cultural practices, sacred sites on the one hand and lucrative development for private interests on the other. As Charlie explained to me, like all else, “farming is political.” Hawaiians Seek Sovereignty Despite their striking parallels to indigenous nations in North America and to Palestinians, Hawai’i is quite distinct. For one, settler-colonialism in Hawai’i does not seek to disappear and replace the native but rather to appropriate and commodify their cultural practices, land/sea-based livelihoods, and images. That is tied to the sovereignty movement, which does not seek to federal recognition as a nation with the benefits of semi-autonomy (think Native Americans and reservations) but rather seeks an end to US occupation and the restoration of national sovereignty. During the summer 2014, the Department of Interior held a series of hearing across the archipelago on this issue and this resistance to federal recognition organically emerged as a consensus. Positive unintended consequences. What next for the Hawaiian movement? The recent DOI hearings revealed a new and organic consensus for independence. Questions remain however, whether that should be a process of diplomatic recognition at the United Nations and among European capitols (think Palestine’s efforts between 2011 and the present) or should it be a movement aimed at ending US colonization by placing Hawai’i on the United Nations list of Non-Self-Governing Territories? Should it be both? What it is the particular role of the Kanaka Maoli in the independence movement and post-independence? Should Hawaiians extricate themselves from a military-industrial economy and if so, how? What is the role of language restoration, environmental justice, and economic justice in these battles? These are all questions Hawaiians are grappling with daily and have been writing about brilliantly. I share a modest reading list below. I am honored that I have met several of these esteemed authors and kahunas. Solidarity With Palestine In the midst of their struggles–Hawaiians have stood in principled and fierce solidarity with Palestinians. Each of my talks was overwhelmingly attended and I was received as no less than a representative of a nation. A humbling and undeserved honor that painfully reminded me that had a vibrant Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) still existed, this may have been possible. In the course of our conversations, Hawaiians expressed that while they see parallels between their struggle and that of Palestinians, they recognize how different they are because they do not endure the violence of military occupation, apartheid, and all out warfare.MANA, the Movement for Aloha No Ka Aina, read this solidarity letter in protest of the war on Gaza at the closing event, which they originally read at a rally protesting a talk by Secretary John Kerry and the US support of Israel’s war on Gaza: August 2014 Movement for Aloha no ka ʻĀina (MANA) is a movement-building organization, established to achieve independence from the United States and social justice in Hawai'i. Hawai'i has been under US occupation for over 120 years, an occupation that is illegal both under international law and US domestic law, a fact that the United States has yet to refute. We follow in the history of Aloha ‘Āina in Hawaiʻi, and in the tradition of peoples throughout the world who struggle for liberation, freedom, and justice. Under US occupation, our people and land have suffered what some might consider a more "tender" violence than what we are currently witnessing in Gaza where the the most explicit of US-backed state violence is being wielded upon Palestinian families. Nonetheless, for the same reasons, for the economic exploitation of our land, the US has systematically repressed our Independence, oppressed Kanaka Maoli, tried to erase us from our land and from our culture and has and continues to drive us and our stories off our lands for housing developments, military expansion, and other corporate interests. To rub salt into the wound, the US military uses our lands to prepare armies around the world to do to other people, what they have essentially done to us. It is both dehumanizing and humiliating to not have control of our own country, to not be able to determine whether our sacred ʻāina will produce food or whether she will be forced into the production of US wars. We are both outraged and strengthened as we witness the Palestinians’ own commitment to struggle to maintain their ancestral connections to land and we are committed to continue to struggle in Hawai'i to liberate our ourselves and our lands toward the liberation of all victims of US empire. They also gifted me with this letter and pair of earrings. And though it was addressed to me, it was meant for a nation on behalf of a nation. I want to end by sharing the poem of Bryan Kamaoli Kuwada- someone I am honored to call a friend and a teacher. Bryan read this poem at the closing event on 1 December 2014 and it is worth sharing many times over. I am also sharing a YouTube clip of his recitation at a different event because watching it is a whole different experience.

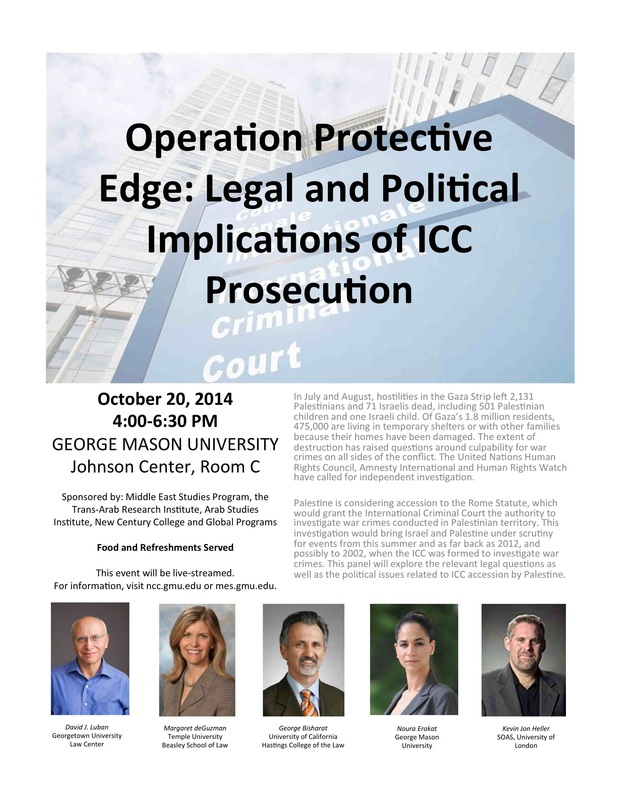

To Ea: In Response to David Kahalemaile, August 12, 1871 By Bryan Kamaoli Kuwada Ke ea o ka i‘a, he wai Lu‘u a ea, lu‘u a ea Breathe deep, O breath-stealing ocean You offer much but exact a toll as well Our friends and our land swallowed by your hungering mouth Too many mistake your surging power for invulnerability And your injuries wash up broken and rotting upon our shores Yet your tattooed knees show that you too have been ignored Sides heaving, coral ribcage expanding, contracting Breathing, an exertion made difficult in this age This era of disrespect, of not honoring reciprocity And those closest to you are those who suffer Until we rise again from your depths Yearning, reaching, crying for ea Ke ea o ke kanaka, he makani Hali mai ka makani i ka hanu ea o ka honua Wind called from our lungs Anae leaping from the pali, two minutes at a time Some lifted on the shoulders of the wind Others clawing for breath as they fall We are taught never to call them back The wind returns, but they do not Mouths stretched open until jaws crack Used as fishhooks, drawing forth our connections from the sea Circular and round, soft and untenable Wind sweeps infinitely into night ‘O ke ea o ka honua, he kanaka ‘O au nō na‘e kāu kauwā In your presence, I count by fours Carrying a breath in each space between my fingers Each palm drawn towards the ground Called close by your fertility Our noses touch Nothing but the ea held in our manawa Cartilage, skin, and bone connecting to rock, earth And young, smooth stone The hā of genealogical age passes between us And I know the weight, the measure, the depth Of my connection to you Ke ea o ka moku, he hoeuli ‘O ka hōkū ho‘okele wa‘a ke a‘ā nei i ka lani Familiar stars and swells etch a map in our aching bones Remembered pain is how we find our way to you Frenzied waves whip the ocean to a bitter froth But we’ve never forgotten how to navigate How to draw our fingers across the face of a passing wave The sun strains as our sail, while birds lift our hulls Koa has always grown on this sea, in our masts, our hulls, our hearts Leaving only the question of crew We accept only those who will step bravely into darkness For we have the generations to light our way Ke ea o ko Hawai‘i Pae ‘Āina, ‘o ia nō ka noho Aupuni ‘ana E ka lāhui ē, ‘o kāu hana nui, e ui ē They tell us that they have seen the wonders of Mānā But it is only heat rippling on sand And we are angry that they are pushing a mirage There is no fucking bucket-- But we have always been crabs Pai‘ea, Kapāpa‘iaheahe, Ka‘a‘amakualenalena Holding fast to the stones, fighting against crashing waves Each struggling breath between sets reaffirms our ea And what they refuse to recognize Is that when we yell, when we shout We do it not in anger But to reassure our ancestors That we are still here Reading Recommendations Liliuokalani, Hawaii’s Story By Hawaii’s Queen. Honolulu: Mutual Publishing, 1990. Goodyear-Kaopua, Noelani, Ikaika Hussey, and Erin Kahunawaika’ala Wright, eds. A Nation Rising: Hawaiian Movements for Life, Land, and Sovereignty. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014. Yamashiro, Aiko and Noelani Goodyear-Kaopua, eds. The Value of Hawai’i 2: Ancestral Roots, Oceanic Visions. Hawai’i: Biographical Research Center, 2014. Haunani Kay Trask, From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawai’i, Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1999. Ku’e: Thirty Years of Land Struggles in Hawai’i, Text and captions by Haunani-Kay Trask, Photographic Essay by Ed Greevy. Honolulu: Mutual Publishing, 2004. Tengan, Ty P. Kawika, Native Men Remade: Gender and Nation in Contemporary Hawai’i. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008. Silva, Noenoe K, Aloha Betrayed: Native Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004. Osorio, Jon, Dismembering Lahui: A History of the Hawaiian Nation to 1887. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2002. J. Kehaulan Kauanui, Hawaiian Blood: Colonialism and the Politics of Sovereignty and Indigeneity, Durham: Duke University Press, 2008. J. Kehaulani Kauanui, “Hawaiian Nationhood, Self-Determination, and International Law,” Transforming the Tools of the Colonizer: Collaboration, Knowledge, and Language in Native Narratives, Ed. Florencia E. Mallon, Durham: Duke University Press, 2011, pp27-53 George Mason University’s Middle East Studies Program, Global Programs, New Century College (NCC) and the Trans-Arab Research Institute welcomed four international law experts to discuss the political and legal implications of an International Criminal Court (ICC) investigation of recent conflict in the Gaza Strip. This discussion was held on Monday, October 20, 2014.

In July and August, hostilities in the Gaza Strip left 2,131 Palestinians and 71 Israelis dead, including 501 Palestinian children and one Israeli child. Of Gaza’s 1.8 million residents, 475,000 are living in temporary shelters or with other families because their homes have been severely damaged. The extent of destruction has raised questions around culpability for war crimes on all sides of the conflict. International organizations including the United Nations Human Rights Council, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have called for independent investigation. Palestine is considering accession to the Rome Statute, which would grant the International Criminal Court the authority to investigate war crimes conducted in Palestinian territory. Such an investigation would bring both Israel and Palestine under scrutiny for events from this summer and as far back as 2012, and possibly to 2002 when the ICC was first formed to investigate war crimes. This panel explored the relevant legal questions under international criminal law as well as the political issues related to ICC accession by Palestine. Panelists included:

|

CurrentsThis is my semi-personal journal of travel, observations, & encounters! Archives

January 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed