|

Introduction

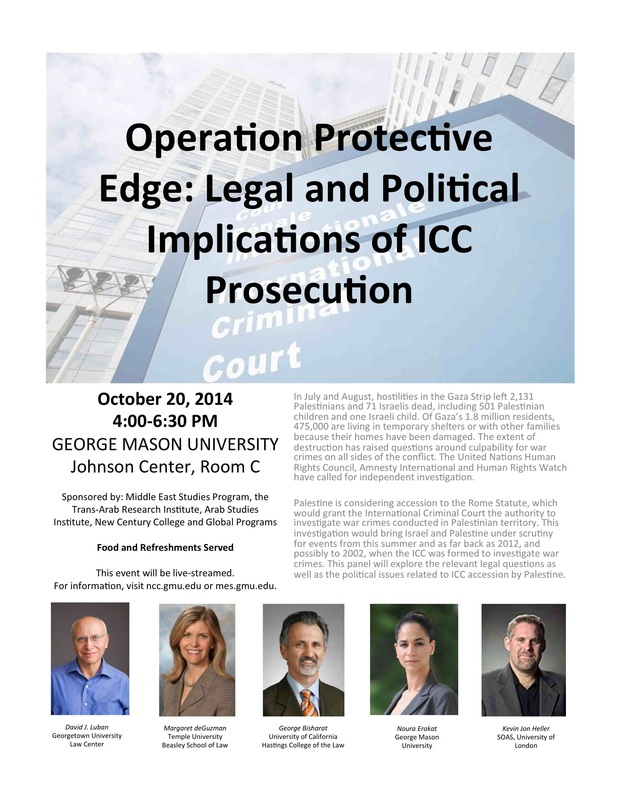

On 23 December 2016, the United Nations Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 2334 confirming the illegality of Israeli settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories, including East Jerusalem, as well as other measures to change the status of these territories. The resolution was sponsored by Malaysia, New Zealand, Senegal, and Venezuela—after Egypt submitted then quickly withdrew the draft text in in order to appease the incoming Trump administration and Israel’s Netanyahu government. The passage of UNSC 2334 marks the first occasion since 1980 that the Security Council has censured Israel’s settler-colonialist practices, primarily because the United States had consistently threatened to use or exercised its veto power against similar initiatives for the past thirty-six years. On this occasion, Washington once again refused to support the resolution—but on account of its abstention, the Security Council was able to unanimously adopt the draft text. In the commentaries below, Jadaliyya Co-Editors Noura Erakat, Mouin Rabbani, and Sherene Seikaly examine various aspects of UNSC 2334, including its broader political and legal implications. Noura Erakat: UNSC Resolution Is Merely an Opportunity by Noura Erakat The most significant aspect of UNSC Resolution 2334 is that it forms the first break with an otherwise absolute US policy to obstruct every Palestinian effort to resist Israeli expansion, especially during the past eight years. During his tenure, President Barack Obama has witnessed and colluded in two massive Israeli onslaughts upon the Gaza Strip, helped shelve the Goldstone Report, and adopted an unprecedented thirty-eight billion US dollars memorandum of understanding with Israel that increases US military aid to it from 3.0 to 3.8 billon US dollars annually over the next ten years. The administration used its first veto in the Security Council in early 2011 to quash a resolution condemning settlements very similar to the one that has just passed, citing Washington’s distaste for internationalizing the conflict. If the Obama Administration was concerned with ushering a new era of the peace process, it would have abstained five years ago and not mere weeks before departing office; or during Palestine’s 2011-12 statehood bid; or in 2015 when it quietly crushed an effort to set a deadline for ending the occupation in the United Nations’s law making body. The administration’s abstention appears more like a finger to US President-Elect Donald Trump and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu rather than a change of heart. At this juncture of its tenure, the Obama Administration only had two embarrassing choices: to veto law and policy it has rhetorically upheld since 1967 or to abstain and expose Israel to international scrutiny. A veto was simply more costly in this instance. The resolution itself does not obligate member states to take action and includes no enforcement mechanisms for the action it recommends. In the wake of the UNSC 2334, Israel is set to approve 618 new settlements in East Jerusalem. So then what does the resolution mean? It all depends on the conduct of the Palestinian leadership. The worst thing it could do is use the opportunity to resuscitate bilateral negotiations under the terms of the Oslo framework. And sadly, all indications point in that direction. But this is an opportunity to break from the self-effacing terms of Oslo and its progeny since 1993. It is an opportunity to take Palestine out of the backwaters of bilateralism and place it back on the international stage. Obamas’ abstention was a theoretical put of the issue out of the US’s absolute scope. The support of New Zealand, Malaysia, Senegal, and Venezuela in the face of Egyptian capitulation, and together with French enthusiasm to carry the mantle in lieu of the United States, indicates an international readiness to shift course. What Palestine needs is a resistance strategy—one that is ready to confront rather than accommodate the occupation and that does not place undue faith in the United States to deliver a solution it has proved unwilling and unable to provide for nearly five decades. It should use this resolution, together with similar initiatives including the 2004 Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) as well as the 2013 UN Human Rights Council Fact-Finding Commission on Settlements to run a diplomatic marathon to pressure states to impose sanctions on Israel in order to highlight, and end, the structural violence of apartheid. It should isolate Israel and delegitimize its settler-colonial project not just to halt and dismantle settlements in the West Bank, but to highlight Israel’s demographic-based policies for what they are: racist and unacceptable. It should use this opportunity to teach the world that the Green Line is imaginary and settlements are not just in the West Bank but also within Israel as demonstrated by the impending wholesale destruction of Umm al-Hieran with the blessing of Israel’s Supreme Court. Netanyahu is already helping on this front by summoning the US ambassador to Israel, reprimanding the ambassadors of states that voted for the resolution, terminating Israeli contributions to five UN institutions and downgrading relations with states that supported the Resolution. He is doing the work of sanctions on our behalf. Unfortunately, the Palestinian leadership does not inspire much hope or confidence. Recall how it sabotaged the Goldstone Report, failed to call for sanctions after the ICJ Advisory Opinion, mourned Shimon Peres rather than highlight his violent and racist legacy, failed to resolve the schism with Hamas, and reified a sinking ship rather than usher a new leadership at the recent Fatah conference. Yet today the ball is in its court, the choice is one between more of the same losing game, or first steps on a much-needed new course that begins by removing Palestine’s eggs from the US basket. Mouin Rabbani: The Significance of UNSC 2334 by Mouin Rabbani US President Barack Obama’s record on the Question of Palestine has been so spinelessly atrocious that it almost makes one nostalgic for the days of Richard Nixon. To credit the United States for United Nations Security Council Resolution 2334, adopted on 23 December 2016, is simply laughable. It is the work of others, which Washington did not support but ultimately chose not to obstruct. There is virtually nothing in the resolution that is new, but that does not make it insignificant. It has been a full thirty-six years since the Security Council last considered the legal status of Israel’s settlements in occupied Arab territory, when UNSC Resolution 465 of 1980 unanimously determined they have none and must be dismantled. During this interregnum Israel’s leaders worked ceaselessly to normalise its colonies and appeared to be making significant headway, particularly in the United States and especially so during the second Clinton and Bush fils administrations. Much of East Jerusalem had been effectively apportioned to Israel by the Clinton Parameters, while Bush in correspondence with Ariel Sharon stopped just short of formally recognizing Israeli sovereignty over most settlements abutting the Green Line. During his own eight years in office Obama indulged Israeli expansionism more than any of his predecessors, thwarting each and every attempt to raise the matter in international fora—including a 2011 veto of a draft UN resolution functionally indistinguishable from the one just adopted. Increasingly exasperated with not only Israel but also the United States, and alarmed by signals emanating from Camp Trump that it intends to detonate the global consensus on the Question of Palestine as well as by Israeli legislative and physical initiatives to make this a reality, the international community decided it needed to confirm certain long-established principles in order to preserve them. We’ll eventually learn why Washington decided to not veto UNSC 2334, but it likely has more to do with Obama feeling personally slighted by Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and prematurely marginalized by President-elect Donald Trump, than with reasons that can be characterized as serious or substantive. Be that as it may, the primary significance of UNSC 2334 is that it sends an unanimous, unambiguous and indeed definitive message from the international community that Israel’s cumulative efforts have resolutely failed to make even a single settlement one shade less illegal than in 1980. This applies equally to what Israel and the United States term “neighbourhoods” in East Jerusalem. Possession may be nine-tenth of the law, but illegal possession, as the Resolution explicitly states, “has no legal validity and constitutes a flagrant violation under international law.” The Security Council resolution in effect amplifies politically the legal conclusions reached on these matters by the International Court of Justice in its 2004 Advisory Opinion on the West Bank Wall. The tsunami of faits accompli Israel has unleashed since 1967 in order to normalize its occupation has therefore, from a legal and diplomatic perspective, achieved precisely nothing. As stated in the Resolution, the international community “will not recognize any changes to the 4 June 1967 lines, including with regard to Jerusalem, other than those agreed by the parties through negotiations”. If and when meaningful negotiations to end the occupation materialize, furthermore, Palestinians will have the right to veto any proposed boundary changes, including land swaps. To dismiss UNSC 2334 as “merely symbolic” does not quite capture the nature and scope of Israel’s defeat; everything it has done to change the status of occupied territory, and achieve recognition of such changes, has been dismissed as meaningless and irrelevant. More to the point, the Resolution provides added impetus and legitimacy to attempts to hold Israel and its officials accountable for their actions, including under Article 8.2(b)(viii) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court that defines settlement practices such as those implemented in the occupied territories as “war crimes”. Unlike Resolution 465, UNSC 2334 does not explicitly call upon Israel “to dismantle the existing settlements”, and only repeats the demand that it “completely cease all settlement activities in the occupied Palestinian territory, including East Jerusalem”. Yet, notes Norman Finkelstein, UNSC 2334 “prominently affirmed the principle of the inadmissibility of acquisition of territory by war, and the US didn't dissent from it”. It therefore seems “the United States no longer supports the interpretation of the operative clause of UNSC 242 that omits the definite article before ‘occupied territories’, as leaving room for Israel to annex territory”. Notably, adds Finkelstein, “inadmissibility was not balanced by the right of all States to live in peace and within secure borders” as it was in UNSC 242. While many have pointed out that the international community has done virtually nothing to implement similar resolutions adopted since the Security Council began censuring Israel’s colonialist practices in 1967, and that this latest resolution too lacks enforcement mechanisms, UNSC 2334 does call upon member states “to distinguish, in their relevant dealings, between the territory of the State of Israel and the territories occupied since 1967”. This entails a clear obligation by states that recognize and/or trade with Israel to differentiatebetween it and the occupied territories, including East Jerusalem. Application of this principle will necessarily require far-reaching sanctions against institutions and corporations based in Israel because these almost uniformly and often deliberately ignore the existence of the Green Line. It also exposes foreign entities that conduct themselves similarly to the prospect of criminal prosecution. UNSC 2334 does not tread any new legal ground but rather confirms established principles and positions—albeit padded with silly references to “incitement and inflammatory rhetoric” to save a gutless American’s face. It is precisely for this reason that the Resolution is above all a political statement. The problem is that—as demonstrated by Egyptian President Abd-al-Fattah al-Sisi’s pathetically craven attempt to kill his own government’s draft resolution—the current Palestinian and Arab leaderships are wholly unqualified to translate its articles into meaningful achievements, and without their lead others are unlikely to follow. The Palestinians will not have another thirty-six years to produce movements, strategies and leaders capable of rising to the occasion. Sherene Seikaly: UNSC 2334 by Sherene Seikaly The legacy of Obama’s presidency is now subject not only to its own imperial machinations but also to the triumph of the right and the celebrity of stupidity that will define Trump’s rule. In the twelfth hour of Obama’s eight-year term, the theater of the United Nations witnessed some unexpected events. First and foremost is the United States government’s abstention on a resolution denouncing the policies of its prodigal child, the state of Israel. It will be this move, while not historically unprecedented, that journalists and commentators will focus on the most. For Israel’s prime minister, it is a source of US betrayal of the now decades long “special relationship” between the two settler colonies. Yet there was another unexpected turn in this late December vote at the United Nations; Egypt’s withdrawal of its own draft resolution shortly after it was formally submitted to the Security Council and just before it was to be put to a vote. It was expected that Egypt’s strongman Abd-al-Fattah al-Sisi would embrace the logic of the leaders he sees himself closest to: Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu and US President-elect Donald Trump. While the Egyptian government had worked alongside the Palestinian Authority to draft the resolution, which after all is simply a reinforcement of conventional international law, Sisi decided to withdraw it at the last hour. His office stated this act came after a telephone call from Trump. Closer observers know that the ties between Sisi and Netanyahu also bore some credit. The two leaders have been fostering these ties since Sisi’s overthrow of Egypt’s first democratically elected president in July 2013. Those ties were at their most explicit during Israel’s brutal assault on Gaza in 2014, when Sisi’s closure of Rafah sealed the only exit for over a million Palestinians in an open-air prison. It was then that Netanyahu insisted to John Kerry that Israel would only negotiate a ceasefire with Sisi. So what then is so unexpected about last week’s Egyptian drama? The shift here comes from Sisi’s unabashed rejection of the rhetoric of state-led pan Arabism. Scholars have long shown that Arab regimes and their initiatives and policies, at best, have been disinterested, duplicitous, and damaging to Palestine and the Palestinians. Egypt is not exceptional in this regard. But Egypt has been the nation that birthed the ill-fated and misguided state-led pan-Arab project. It has been a nation whose citizens have sacrificed lives and limbs in various wars and conflicts. It has been a nation that has served as the intellectual and cultural refuge for so many Palestinians. For Egypt to withdraw a resolution confirming the illegality of Israeli settlements in occupied Palestinian territory, is a rhetorical first. It is effectively, the final unmasking of the long-standing fallacy of regime led pan-Arabism. Since that fallacy has been rotting for decades now, perhaps Sisi has done us a favor. We can finally leave the wake and bury the corpse.

10 Comments

In mid-July 2016, we, a group of scholars, activists, and artists from the United States, Belgium, and Palestine, released a pedagogical project entitled Gaza in Context. The project aims to upend an ahistorical narrative that has cast the Gaza Strip as a national security issue. By emphasizing the role of Hamas and diminishing the question of Palestine, Israel has collapsed conditions in Gaza with asymmetric conflicts, or what has come to be known as the “global war on terror,” thus eliding the consequential distinctions between Palestinians and other non-state actors. This pedagogical project is an attempt to re-frame the issue in order to place greater emphasis on the broader question of Palestine and to explain Israel’s policy towards the Gaza Strip in a settler-colonial framework. A 20-minute multi-media film that combines lecture, animation, typography, and footage from Palestine is the centerpiece of this project. The short film is also available in four, five-minute parts and each part corresponds to a teaching guide for instructional purposes. Other components of the project include abibliography featuring 110 entries that include books, journal articles, book chapters, essays, films, lectures, and videos as well as a compendium of Jadaliyya articles featured in what we call a JadMag. All of these elements are housed on the project’s own website, which is part of a larger research project on Palestine headed by the Forum on Arab and Muslim Affairs at the Arab Studies Institute. The project received warm endorsements from academic, advocate, and activist luminaries, Sara Roy, Raja Shehadeh, Richard Falk, Nadia Hijab, Diana Buttu, as well as Robin D.G. Kelley, who commented: Gaza in Context should be required viewing for everyone, including those familiar with the situation in Palestine. Powerful, informative, and persuasive, Noura Erakat delivers a fusillade of facts with concision and passion, obliterating in twenty minutes some three decades of media misinformation about Israel’s occupation of Palestine. An effective teaching tool, irrespective of one’s political position. The project received broad international coverage including the following pieces:

The Nakba marks a momentous rupture in the history of Arab connection to the land of Palestine. The forcible, mass removal of native Palestinians in 1948 thus overwhelms the history, literature, activism, and memory regarding the Palestinian Question. To begin in 1948 is to narrate a story of collective loss, one that gives vivid expression to the collusion of state powers, the asymmetric capacities between industrialized and developing nations, the unyielding sway of nationalism, and to the remarkable expendability of certain human life.

While these expressive lessons are particular to Palestine and Palestinians, they are also plainly unexceptional. The question of Palestine is like so many other case studies of settler-colonialism, institutionalized racism, and state-led practices of systematic dehumanization. And so many other case studies are like Palestine in their modalities of repression and technologies of violent domination. If, indeed, there is no Palestinian exception, what does that freedom from anecdotal particularity afford us in the way of understanding the conflict and its possible solutions? One productive approach is to try to understand how anti-blackness informs the conflict. Here I draw on the work of afro-pessimists who have theorized anti-blackness as an analytical framework with a focus on the afterlife of slavery in the New World. This framework informs how the nation-state comes to embody technologies of power, coercion, and violence that determine death and the possibilities of life. Scholar Rinaldo Walcott explains: “What it means to be human is continually defined against Black people and Blackness….It is precisely by engaging the conditions of the invention of blackness, the ways in which its invention produces the conditions of unfreedom and the question of how those conditions produce various genres of the Human, genres that are continually defined against blackness, that any attempt to engage a decolonial project may avoid its own demise.” This framework urges us to rethink Zionism so that it is not just a settler-colonial movement predicated on the forced removal and annihilation of the native, but also a nationalist movement predicated on the racialized tropes deployed against Jews of Europe. An anti-blackness framework also urges us to think about other communities, besides native Palestinians, that intersect with the category of “black.” People of African descent have long been in Palestine/Israel, and their presence cuts across dominant categories: there are Afro-Palestinians (predominantly Muslim), Ethiopian Israeli Jews (whose mass migration begins to achieve momentum in the mid-eighties), and recently-arrived asylum seekers from Sudan and Eritrea (both Muslim and Christian). Such provocations unsettle a stark native-settler binary and illuminate broader implications for anti-racist commitments within the Palestinian liberation struggle. Israeli Jewish society features a stark socio-economic and racial hierarchy. It includes Western European Jews, African Jews, Middle Eastern Jews, and Russian Jews, as well as other social groups like non-Jewish foreign workers. The oppression these groups experience cuts across various intersecting axes of race, class, gender, national origin, as well as other distinctive markers. Palestinians, including citizens of Israel, do not represent the most extreme site of oppression in this social order; rather, they are outside it altogether. They constitute a baseline equivalent with social death because of the extreme institutional deprivation they endure, which denies them access to opportunities, movement, family, nationhood, land, livelihood, and security in the physical and metaphysical sense. Palestinian nationalism equips us to resist this dehumanizing framework by exposing the annihilationist logics of Zionist settler-colonization and demanding a restoration of indigenous sovereignty. It does not, however, adequately grapple with the racial logics that mediate Palestinian deprivation and Israeli socio-racial stratification. Among liberal Zionists, the treatment of Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip is a matter of foreign policy, while racial discrimination, against Palestinians with Israeli citizenship and African descendants, is a domestic issue. In a Palestinian nationalist framework, Afro-Israelis and asylum-seekers might be seen as settlers, even if relatively less privileged ones, and Israel’s violent exclusion of them demonstrates its constitutive race-based logics. But what is the connection, if any, between the exclusion and discrimination against these native and settler classes? Borrowing from afro-pessimist works on the condition of being human, we may reconsider Zionism as a civilizational project that reifies the ineligibility of Jews for European whiteness even as it divests Palestinians of any material or metaphysical value. As a derivative of Enlightenment Europe, Zionist nationalism reproduced the polarized binaries of the superior, enlightened West and the inferior, primitive East. It claimed that Jews as a national entity belonged to the superior, enlightened West despite their geographical origins in the East, and sought to enlighten (read: colonize) its primitive peoples. Accordingly, Zionist ideology inferiorized the non-Western Jew, and aimed to civilize her by erasing her difference, just as Enlightenment Europe had sought to do with its Jewish population. It combated anti-Jewish bigotry by internalizing and reproducing it. The nationalization of Judaism (Israel refuses to recognize an “Israeli” nationality, only a Jewish one, as confirmed by the Supreme Court in the Ornan case) nevertheless ascribed significant value to Eastern and African Jewish identity; they remained superior to the Palestinian native. Zionism consecrated Jewish nationality in law and strictly regulated its acquisition and the myriad entitlements that flow from it. Palestinians who lacked Jewish nationality were not eligible for rehabilitation, or whiteness, at all, and had to be removed, dispossessed, and/or contained. The Palestinian body, as a site of exploitation, dispossession, and precarity, lacks material value. The value of Jewish nationality, and, by extension, Israeli Whiteness, directly correlates to the deprivation of Palestinian land, presence, and nationhood. Structurally, therefore, the approximation of whiteness within Israel necessitates the ongoing deprivation of Palestinians. And the deprivation of Palestinians reproduces and reifies the logic constitutive of Israel’s racial hierarchal regime. Settler-decolonization affords an opportunity for emancipation from the fundamental assumptions of white supremacy by addressing the very racial logics that presuppose Jewish inferiority to European Whiteness. Destruction of the colonial relation that facilitates systematic Palestinian deprivation should thus subvert those disfiguring oriental tropes that positioned Jews as outsiders in Europe and, later, as colonial masters in the Middle East. Such a movement aims not only to unsettle a native-settler relationship, but also to unsettle the system of stratified value measured against it. Under such a framework, Jews are able to resist, rather than embody, the racial logics that produced their exclusion within Europe and that continue to stratify Israeli society. This is also a worthwhile inquiry in light of the resurgence of Black-Palestinian solidarity. It helps navigate the responsibilities that may inhere to the Palestinian movements claiming such solidarities. For example, without scrutinizing the modalities of anti-blackness, non-black Palestinians may risk reifying these institutionalized systems of dehumanization. Palestinian proximity to social death makes Palestinians the non-human, figurative black body in this moment in Israel/Palestine. However, unlike their Afro-Palestinian, Afro-Arab, Afro-Israeli, and African diaspora counterparts more generally, this status is contingent rather than global. Like the Eastern Jews who are eligible for modified whiteness within a Zionist schema, Palestinians view national sovereignty as means for their own aspirations to contingent whiteness. There is therefore an inherent risk within the Palestinian movement for settler-decolonization of reifying anti-blackness: in seeking to overthrow the yolk of Zionist settler-colonization without addressing the racist logics motivating its annihilationist assumptions, Palestinians risk restoring indigenous sovereignty and reproducing the same state structures predicated on dehumanizing a putative other. Not all settlers are the same. Removing the settler without combating the supremacist logics that facilitated her presence risks leaving those logics intact. Mapping possible strategies and frameworks that address these risks is a critical task for the Palestinian movement. Worthwhile questions include what is the proper place of African Jewish-Israelis and African asylum-seekers in an anti-Zionist framework? What are the possibilities and limitations of coalition with Middle Eastern Jews? How does attention to or elision of Afro-Palestinian communities inform understandings of Palestinian liberation? These are all questions that help to guide our thinking beyond the Palestinian exception and to use the practice of Palestinian struggle and resistance as a platform for addressing liberation not just for a nation, but, more broadly, for humanity’s expendable populations. For further reading: Noura Erakat, Whiteness as Property in Israel: Revival, Rehabilitation, and Removal, 31 Harv. J.Racial & Ethnic Just. 69 (2015). This video project is the culmination of over a year's work with an incredible team of writers, media advocates, music producers, film editors, and lots and lots and lots of solid friends. We dropped it on 14 October 2015 and it went viral, so to speak. The media coverage was extensive because of the noteworthy participants in the video and the fact that the project built on a mounting legacy of movement building between Black and Palestinian communities. Here's a blurb about the video from the website: Black-Palestinian solidarity is neither a guarantee nor a requirement - it is a choice. We choose to build with one another in a shoulder to shoulder struggle against state-sanctioned violence. A violence that is manifest in the speed of bullets and batons and tear gas that pierce our bodies. One that is latent in the edifice of law and concrete that work together to, physically and figuratively, cage us. We choose to join one another in resistance not because our struggles are the same but because we each struggle against the formidable forces of structural racism and the carceral and lethal technologies deployed to maintain them. This video intends to interrupt that process – to assert our humanity – and to stand together in an affirmation of life and a commitment to resistance. From Ferguson to Gaza, from Baltimore to Jerusalem, from Charleston to Bethlehem, we will be free. Here's a media round up of the coverage of the video:

In their forthcoming paper, The Tyranny of Context: Israeli Targeting Practices in Legal Perspective, Michael Schmitt and John J. Merriam examine Israel’s targeting practices against the Gaza Strip and Lebanon. Their purpose is to scrutinize the context in which these attacks take place as well as the Israeli Army’s relevant legal standards regulating them.

Their findings are based on two visits to Israel in December 2014 and February 2015. During those visits, the Israeli Army granted them: …unprecedented access that included a “staff ride” of the Gaza area, inspection of an Israeli operations center responsible for overseeing combat operations, a visit to a Hamas infiltration tunnel, review of IDF doctrine and other targeting guidance and briefings by IDF operations and legal personnel who have participated in targeting. The authors also conducted extensive interviews of senior IDF commanders and key IDF legal advisers. (3) The methodological approach should raise, at least, a few red flags. Schmitt and Merriam are aware of their problematic methodological approach and write: Although the approach might be perceived as leading to a pro-Israeli bias, the sole purpose of the project was to examine Israeli targeting systems, processes and norms in the abstract; no attempt was made to assess targeting during any particular conflict or the legality of individual attacks. (3) In essence, they acknowledge that this entire paper examines what IDF lawyers say rather than what IDF operators do. At best – we should read it as a supplementary report to the Israeli Army’s war manual: it is just theoretical. That may be acceptable, but the authors go on to say: With respect to the resulting observations and conclusions, note that the authors combine extensive academic and operational experience vis-à-vis targeting and therefore were in a unique position to assess the credibility and viability of Israeli assertions. The result was a highly granular and exceptionally frank dialogue. (4) So what they tell us at first, that this paper is just “in the abstract,” they also claim is “granular and exceptionally frank.” Moreover, they claim that their combined experience enables them to assess the “credibility and viability” of Israel’s claims. This is an arguably impossible task if they do not assess Israel’s assertions about their practices in comparisons to actual practice. In fact, the next fifty-some pages read like an estimable apology on Israel’s behalf. The authors accept nearly everything their respondents say, and even what they decline to say, at face-value. The authors assert the authoritative nature of their findings although they do not interview a single Palestinian or Lebanese civilian who has been subject to Israel’s military attacks. They do not even bother to review the reports describing Israel’s operational practices. Several of those reports have alleged that Israel’s practices constitute war crimes. The words “war crimes” appear only twice in the paper: in the titles of articles they cite in their footnotes. Their exceptional reference to Human Rights Watch or Amnesty International reports are primarily to support claims regarding attacks on Israel by Hamas or Hezbollah. As my colleague and legal scholar on laws of war explained to me, he has become accustomed to reading such reports like an anthropologist. Indeed, the value of this paper is its insightful display of the production of knowledge on national security and counter-terrorism from the US and Israeli metropolises. While this may be reason to dismiss the paper all together, it is also precisely why the paper merits response. Schmitt and Merriam are hardly insignificant. Their tremendous body of scholarship and influence means that their interventions will be taken very seriously and will inevitably bear upon the ways we come to understand, justify, and/or reject the development of the laws of armed conflict. This short piece aims to use three select examples to highlight the methodological shortcomings that give rise to insufficiently tested findings that are emblematic of the paper. For the sake of specificity and fidelity to context, I will focus just on Operation Protective Edge, Israel’s 2014, 51-day attack on the Gaza Strip. 1) “The single most important facet of warfare from Israel’s perspective is the proximity of the threat.” In this passage beginning on page 5, Schmitt and Merriam discuss the implications of proximity of the threat emerging from the Gaza Strip. They assess that such proximity denies Israel the advantage of “expeditionary force” and, therefore, it must be prepared to fight “…within minutes, and sometimes within view, of their homes.” Conversely, this spatial reality affords Israel the benefit of interior position or, “the virtue of enabling one to concentrate forces quickly and maneuver them in any direction the situation may warrant.” Schmitt and Merriam discuss the military implications of the Gaza Strip’s proximity but fail to address its fundamental nature: Israel’s military occupation. The Gaza Strip is the western-most frontier of Mandate Palestine that Israel did not conquer in the 1948 War, which it subsequently occupied in 1967. The coastal enclave is proximate because Israel established itself in the area already inhabited by native Arabs and who were promised self-determination under the League of Nations Mandate system. This history matters for two reasons. Firstly, this history brings into play the right of a people under alien occupation and colonial domination to use force in pursuit of their self-determination captured in Article 1(4) of Additional Protocol I. This provides the legal justification for Palestinians to use force against Israel. Notably, the authors mention this right much later in the paper where they muse whether Israel’s opposition to Article 1(4) mirrors the U.S.’s position, that national liberation movements lack the resources and accountability mechanisms to fulfill the duties and obligations of international law. While they do not resolve this issue, they note, Although not directly bearing on the issue of Israeli targeting, note that the Israeli position deprives members of national liberation movements of any belligerent immunity for their attacks on Israeli targets, including those that qualify as military objectives. (31) They do not raise the obvious conundrum that Israel’s position simultaneously incapacitates the Palestinian population from using force, even with weapons capable of precision-strikes, while fully and arbitrarily subjecting them to Israel’s military prowess. In fact, they qualify this condition by claiming that it does not bear “on the issue of Israeli targeting” at all. Schmitt and Merriam note this without irony as they discuss the “tyranny of context.” Secondly, the status of the Gaza Strip, namely whether or not it is occupied, impacts Israel’s permissible use of force against it. The authors say that Hamas has been in control of the coastal enclave since 2007 but fail to probe whether that control is tantamount to the cessation of occupation under the Geneva Conventions. While Israel has insisted that its occupation ended upon its unilateral withdrawal in 2005, numerous scholars (seehere, here, and here) as well as the Office of the Prosecutor and the Human Rights Council Fact-Finding Mission to Gaza have insisted that the occupation continues and remains consequential. In sum- if the territory is occupied, Israel has the duty to protect the civilians under occupation and in cases of unrest, it can use law enforcement authority to resume order. In contrast, if it can invoke self-defense in law (UN Charter and/or customary law) then it can resort to military force. Notably, since 2001 Israel’s High Court has insisted that it can apply both the law of occupation to govern the Occupied Territory as well as the law of armed conflict (LOAC) to quell unrest. (Can’an v. IDF Military Commander). By 2005, they find that LOAC supersedes Occupation Law. (Public Committee Against Torture in Israel v. The Government of Israel). This means that it can deny Palestinians the right to govern themselves and simultaneously use military force to thwart their resistance to military rule. Israel’s High Court has been in lockstep with its Government in maintaining a military occupation and deeming it a war against terror. Context here is consequential. The Gaza Strip is not proximate to Israel by random fortune- but because Israel established itself in Mandate Palestine by war and literally removed and dispossessed its native Palestinian inhabitants. This conquest remains contested by Palestinians and that is the root source of ongoing conflict.What Schmitt and Merriam swiftly disregard as proximate asymmetric violence is in fact the function of ongoing and unresolved claims over Israel’s authoritative jurisdiction. Obscuring this context risks creating a new body of law intended to protect a power’s colonial holdings as it gives the impression that Israel is using force to defend itself when, in fact, it is using force to squash Palestinian claims and militarily resolve the dispute over its control. Simultaneously, Israel criminalizes all Palestinian use of force in response, or otherwise, as terroristic. The authors in/advertently reify this false and counterproductive narrative without scrutiny. 2) “…[C]asualty-aversion leads Israel to liberally apply force…” In the same section on operational context, Schmitt and Merriam explain that the Israeli Army is a conscript force. The diffuse and shared nature of military service shapes Israeli values and thus how Israel engages in warfare. In particular, the public’s aversion to soldier casualties “…leads Israel to liberally apply force, particularly airstrikes and counter-battery fire, in order to ‘guarantee force protection.’” (8) This, the authors explain, also impacts Israeli sensitivity towards captured personnel and shaped the Hannibal Doctrine- the operational doctrine wherein the mission is to rescue a soldier from captivity at all costs including (fatal) injury to Israeli personnel. While Schmitt and Merriam do not explicitly say so, the proposition above unduly shifts the risk of warfare from soldiers to enemy civilians; an incredibly controversial position. So much so that it occupied a series of essays and responses between the authors of the proposition and other legal scholars. Proportionality in ongoing hostilities demands that a belligerent’s military advantage outweigh the harm it causes to civilians and civilian infrastructure. Under Israel’s force protection rubric, its military advantage includes heightened security afforded to its soldiers. While all armed forces consider force protection as part of its military advantage, Israel’s proposal is radical in that it considers its soldiers lives to be more valuable than those of enemy civilians. Therefore, when assessing proportionality, it tolerates greater numbers of civilian deaths and injuries so long as that spares its soldiers from harm. The outcome of this almost ensures devastating results. At the most extreme end of this proposition is that a belligerent force could carpet bomb its adversary for the sake of preserving their soldiers’ lives, thus destroying those gains achieved by anti-colonial struggles and captured in Additional Protocols I and II. Colonized and occupied peoples would thus be subject to nearly unregulated military force. Consider the testimony of sixty Israeli soldiers who fought in the 2014 Gaza Offensive testified to very lenient rules of engagement including directives to “shoot at anything that moves.” These rules of engagement may very well reflect Israel’s radical force protection proposition. Notably, Israeli forces killed approximately 2,100 Palestinians, including 504 children during Operation Protective Edge. Schmitt and Merriam do not take serious issue with this proposition. In fact, they do not mention the implications of Israel’s force protection until some 35 pages later in their section on Proportionality. There, they simply note their surprise and then their passive acceptance for the novel approach: Both authors were struck by the weight of accorded in the proportionality analysis to the military advantage of protecting the civilian population and individual soldiers. Although they would not label it unwarranted in light of the unique operational context in which Israel finds itself, it was clear to them that avoidance of harm to the Israeli civilian population and the protection of individual soldiers loomed large in Israeli proportionality calculations. (45) Among the examples they provide to demonstrate the application of this approach is Israel’s deadly operation in Rafah where its Army applied the Hannibal Doctrine. Schmitt and Merriam mention that Israel’s rules of engagement “…reportedly resulted in as many as 114 deaths in Rafah.” (46) They say nothing more about the significance of these civilian losses that may put Israel’s proposition into question. For example, they do not share that the Israeli Army admitted to sealing off a 1.5 mile radius so that no one could flee. Nor did they say that according to an Israeli officer, they released 500 artillery shells onto the area over the next eight hours, nor the fact that they also conducted 100 airstrikes over the course of two days. They do not mention that the commander of the Givati Brigade said to the Associated Press "That's why we used all this force…Those who kidnap need to know they will pay a price. This was not revenge. They simply messed with the wrong brigade." Israel’s proportionality assessment has had horrifying consequences. Schmitt and Merriam discuss nothing of this and simply state that Israel factors in “rescue and survival” into its military advantage in ways that would tolerate greater collateral damage. One of the authors agrees with the Israeli Army’s approach and the other believes that this is only significant for determining “the military feasibility of precautions in attack…” (46) Neither author critically assesses the unprecedented harm this approach would impose on civilians caught in warfare especially those civilians caught in anti-colonial struggles. 3) “The civilians are hopefully frightened into dispersing.” In their discussion on aerial targeting practices, Schmitt and Merriam discuss Israel’s “knock on the roof” policy. This is the practice of shooting a missile at a home or building in order to warn the civilians of an impending strike. The policy is highly controversial. The relatively small rocket causes damage. A rocket in and of itself, regardless of the size has the impact of causing shock and often paralysis. When used by Israel, the larger rocket usually makes impact 45 seconds to three minutes later not providing adequate time to flee. In some instances, no rocket follows and the small rocket can constitute psychological warfare upon Palestinians. The authors discuss none of these details. In fairness, they describe the technique as “controversial.” They write The technique involves employing small sub-munitions that impact one corner of the roof and detonates as very small explosions that produce noise and concussion, several minutes ahead of the strike. The civilians are hopefully frightened into dispersing. Once they have cleared the target area, the IDF launches the attack. (17) The authors go to great lengths to downplay the size and scope of the rocket. They implicitly suggest that the Israeli Army waits for the civilians to leave before launching the second and larger missile, and explicitly say so in their footnote. This has hardly been the case as indicated by the numbers of Palestinians killed in their homes. The most troubling part of this passage, however, is their comment that the “civilians are hopefully frightened into dispersing” indicating an ambivalence about the efficacy of the warning technique while simultaneously acknowledging its psychological impact of creating fear. The authors characterize this practice as legal because it is incidental to a legitimate military objective. In contrast, they concur with Israeli legal advisers that the fear wrought by Palestinian rockets is illegal, even if they do not pose a deathly threat, because they intend to cause fear. (45) Reference to empirical evidence undermines these findings. Based on their investigation, for example, the FIDH concluded that “rather than minimising loss of civilian life, Israel’s warning policy fomented massive forced displacement and spread confusion and fear among the population.” (23) OCHA reported Throughout the conflict there was a real fear among the population that no person or place was safe, as evidenced by attacks on hospitals, residential buildings and schools designated as shelters. Psychosocial distress levels, already high among the population of Gaza, have worsened significantly as a result of the conflict. Later Schmitt and Merriam claim that the technique is used exceptionally when other warnings have proven futile- this based solely on what their Israeli interlocutors have told them. They then claim, as a matter-of-fact, that “the technique is only used when the building has been converted into a military objective through use (such as weapons storage)” again based solely on Israeli intelligence. (49) A cursory reading of any of the reports and commentary conducted on Israel’s warning system, or lack thereof, would provide a completely different assessment. (See e.g., United Nations, Amnesty International, B’tselem, Al Mezan, Human Rights Watch, FIDH). The authors defend the fact that Israel does not always afford adequate time to flee. They explain this situation typically arises …when the enemy is using the warnings to either know when and where to use human shields or take measures to prevent the civilians there from leaving. Such practices may leave only a narrow window of opportunity to strike before the number of individuals likely to be harmed in the attack rises. Therefore, a strike soon after a warning may in certain circumstances be the best means for minimizing civilian injury even when it does not afford civilians a great deal of time to leave or take shelter. (49) Schmitt and Merriam are making an absolute proposition: when Israel forces believe necessary to achieve their military objective, they must strike immediately even if civilians do not have time to flee or a place to shelter. They implicitly suggest that in such a case, Israel is relieved of its duty to assess whether such harm is proportional because it issued a warning, essentially giving its forces free reign to use force. Had the authors considered operational practice it may have included a discussion of the United Nations’ Board of Inquiryfindings. That investigation concluded that Israel indeed struck seven UNRWA schools, several providing shelter to civilians, and none were storing weapons or militants. Israel responded that it was investigating these claims. How does this operational practice recalibrate the authors’ analysis? How can we take their findings seriously if they are not even considered? The paper is rife with similar examples: explanation/apology for Israel’s rules of engagement without examining their application in operational practice. Schmitt and Merriam’s omissions merit much deeper scrutiny and engagement. Just scratching the surface reveals their flawed methodological approach and the inadequate engagement with the implications of their findings. In the best-case scenario, readers will approach their essay like a supplement to Israel’s Army Manual and read it with leisurely interest. In the worst, and more likely scenario, this work will significantly bear upon the production of knowledge regarding national security and humanitarian law and have fatal and devastating consequences. This does not only bear upon Israel’s wars but especially those waged by the United States against both state and non-state actors. For this reason, we should treat this essay with the alarm it merits. Originally Published on Jadaliyya on 18 June 2015 Moderated by Noura Erakat